[ad_1]

Penguin Random House

Penguin Random HouseWinston Churchill’s aristocratic daughter-in-law and confidante Pamela Harriman is considered “the greatest courtesan of her era”. Decades after her death, she still divides opinion – was she a smart power player, or “shameless” and “repellent”?

You could call her by her six names: Pamela Beryl Digby Churchill Hayward Harriman – a British aristocrat who ended up a Washington power player and the US ambassador to France, having touched many famous lives in 20th-Century politics and culture. When she was just 20, her father-in-law Winston Churchill engaged her as “his most willing and committed secret weapon” (as a new biography puts it) and during World War Two she wined, dined and seduced important Americans, winning them over to the British cause against the Nazis. And later, her impact extended further, as she interacted with public figures including the Kennedys, Bill Clinton, Nelson Mandela and Truman Capote – who eventually satirised her in his fiction, alongside his other “swans”.

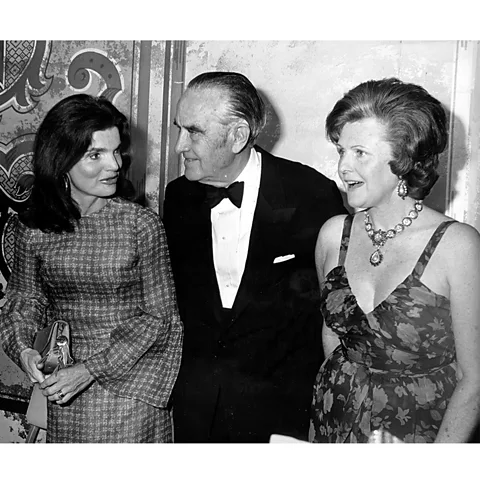

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMore than 27 years have passed since Pamela Harriman suffered a fatal brain hemorrhage while swimming in the pool at Paris’s Ritz Hotel, yet she remains a divisive character, as evidenced by the varied reactions to Sonia Purnell’s new biography, Kingmaker: Pamela Harriman’s Astonishing Life of Power, Seduction, and Intrigue. To some, the book reads as an appreciation of an influential life lived boldly, cannily and ambitiously in Britain, elsewhere in Europe, and the US. Others find it unduly praising of a woman who used sex to advance herself and whose political impact, they say, is overstated.

Born to a cash-strapped baron in 1920, and bred to “marry well”, Pamela failed to find a husband during her first London “season” in 1938. Nancy Mitford, the most sharp-tongued of the famous Mitford sisters, described the teenage Pam as a “red-headed bouncing little thing”. The following year, Randolph Churchill, only son of the famous Winston, telephoned her to ask for a date. Convinced he’d be killed in the war which had just been declared, Randolph was anxious to have a son. Over dinner with Pamela, he came quickly to the point. Purnell writes: “He didn’t love her… but she looked healthy enough to bear his child.” Pamela, eager to escape a deathly-dull life with her parents in deepest Dorset, took the deal.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHer gamble paid off, although not in conjugal bliss. Randolph, a drunk and a troublemaker, treated her contemptuously before and after she gave birth to baby Winston. But once her father-in-law became prime minister in May 1940, Pamela landed in the room where everything happened. “Nobody ever had a chance to see politics as much from the inside as I did,” she said later.

Britain at that time stood alone against the Nazi war machine, and Churchill urgently needed transatlantic aid, which was not immediately forthcoming. After the fall of Paris, polling revealed that the US electorate was even less keen than before to join the Allied cause.

Pamela knew the stakes. “If and when America came into the war, then the war would be safe. As long as they weren’t in the war, it was precarious,” she later recalled. Churchill doted on his cheerful, dewy-skinned daughter-in-law. He negotiated that a winsome portrait of Pamela with her infant son (taken by Cecil Beaton, the royals’ favourite photographer) grace the cover of Life, then the US’s largest-circulation magazine. He also had his ally Lord Beaverbrook fund a new wardrobe for her. She flattered the first envoy who Roosevelt sent to Britain, Harry Hopkins, who found her “delicious”. And when wealthy Averell Harriman came to London in March 1941 to administer the aid program, the lifeline Churchill so desperately needed, Pamela made a point of getting to know him.

After Pamela, then 21, embarked on an affair with the married Harriman, 49, the Prime Minister, eager to learn what Harriman was saying and doing, would debrief Pamela over late-night two-handed card games. Reviewing Kingmaker for The Times, Roger Lewis dismisses the idea that Pamela fed her father-in-law vital intelligence, and describes her as a “a mercenary sex obsessive”.

Alamy

AlamyFrank Costigliola, professor of history at the University of Connecticut and author of Roosevelt’s Lost Alliances: How Personal Politics Helped Start the Cold War, tells the BBC: “Pamela was a tremendous asset to Churchill given the importance of information in wartime. To think otherwise is to be ignorant of the history, and smacks of misogyny.”

Purnell doesn’t dispute Harriman’s sexual exploits, recalling in Kingmaker how she became known as “the greatest courtesan of her era”. Journalist Harrison Salisbury famously recalled that during World War Two in London, “sex hung in the air like a fog”. So Pamela was hardly unusual in falling into bed with a new partner, though she was probably an outlier in the frequency with which it happened. The (partial) list of her lovers included Edward R Murrow, the CBS broadcaster (“This is London”), Major General Fred Anderson, commander of the American bombing force, Colonel Jock Whitney, intelligence officer with the OSS, and Murrow’s CBS boss Bill Paley, who was on General Dwight D Eisenhower’s staff.

What information Pamela passed on to Churchill – or what he requested she tell the powerful Americans with whom she was intimate – remains unknown, but, Purnell writes: “Her pillow talk was reaching the ears of leaders and influencing high-level policy on both sides of the Atlantic.” In his review, Lewis brands this as “hyperbole”, although it is notable that when Randolph Churchill eventually learned of his wife’s adultery with Harriman, he berated his parents for their complicity.

American dream

Divorced after the war, Pamela decamped to Paris, and became part of a cosmopolitan set, having affairs with a roster of rich men, including Prince Aly Khan, Gianni Agnelli and Élie de Rothschild. These paramours financed her luxurious lifestyle, but none would put a ring on her finger. Approaching 40, she convinced Leland Hayward, a successful Broadway and Hollywood producer, to leave his glamorous wife Nancy – nicknamed “Slim” – for her.

Both Pamela Hayward, as she was then called, and Lady Slim Keith – now married to British banker and aristocrat Kenneth Keith – counted among “the intercontinental covey of swans” first described by writer Truman Capote in an October 1959 issue of Harper’s Bazaar. Seriously rich, seriously beautiful, and seriously elegant, these society ladies loved Capote, and relied on him as an escort and confidant – until he went public with their secrets.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHayward’s career and health declined precipitously in the decade after he married Pamela, but she remained loyal. Even Brooke Hayward, Pamela’s step-daughter, who in her best-selling memoir Haywire accused Pamela of absconding with some family jewellery (along with other misdemeanours) acknowledged this. “Pamela had a great gift: she understood the men she loved. That was where she began and ended; it was the only life she had,” Hayward wrote.

After Leland’s death, in spring 1971, Pamela’s journalist neighbour Lally Weymouth saw that she was “miserable”. Her mother, Washington Post publisher Katharine Graham, was throwing a party, and Weymouth urged Pamela to attend in her place. There, Pamela encountered Averell Harriman again. He had been widowed the year before, and the two former lovers promptly rekindled their relationship, marrying a few months later. “It became Washington folklore that Pamela had lobbied for the invitation as a ruse to meet Averell,” Purnell writes. “As so often, the rumours about Pamela were salacious enough for many not to worry whether they were true.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe new Mrs Harriman endured something of a humiliation when Capote’s short story La Côte Basque 1965 appeared in Esquire magazine in 1975, with the heartless Lady Ina Coolbirth – a composite figure, elements of whom resembled Harriman – at its centre. But during the final two decades of her life, Pamela became a power player in Washington. Backed by the Harriman millions, she began funding and championing candidates of the Democratic party after Republican Ronald Reagan won a landslide presidential election in 1980. Among her favourites: two future presidents, Joe Biden, then a senator from Delaware, and Bill Clinton, then the governor of Arkansas.

This robust third act culminated in her appointment as ambassador to France by a grateful Clinton. And while a faithful and attentive wife to the ageing Harriman, Pamela was still labelled by Ben Bradlee, longtime editor of The Washington Post, as someone whose politics were “between her legs”, writes Purnell in her book. Thomas Mallon, a historical novelist and essayist, reviewing Kingmaker for The Washington Post, wrote that the book did not “cope with the peculiar deadness inside such an apparently vital subject, one whose remorseless, mechanical nature still renders her, even at this long remove, more repellent than fascinating”.

Purnell feels her book’s sometimes hostile reception has meant her experiencing “a tiny fraction of what Pamela went through”, she tells the BBC. And after reading her papers and letters, now kept at the Library of Congress, Purnell came to like her subject more and more.

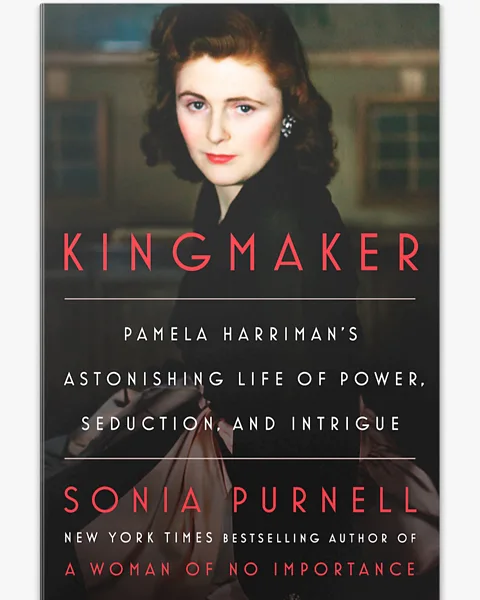

Penguin Random House

Penguin Random HousePerhaps Pamela’s life is a kind of Rorschach test. How does the enduring double standard strike you? As Leamer points out: “It’s still true: If you sleep with a lot of people and you’re a woman you’re a ‘slut’, but if you’re a man you’re a ‘stud’.” And on what terms should you judge a woman from another era? Pamela was clearly attracted to power from an early age and, meagerly educated as she was, there was little opportunity then to pursue it on her own.

Pamela’s own self-assessment is revealing. Speaking to Michael Gross in New York Magazine in 1992, and later quoted in The New York Times, she said: “Basically, I’m a backroom girl. I’ve always said this and I’ve always believed it. I prefer to push and shove other people. I don’t really like to be put forward myself. I was very happy to be the wife of the two husbands I loved.”

[ad_2]

Source link