[ad_1]

More than 1,000 people walked in sacred silence through Milan, their black shirts illuminated by flaming torches. Those towards the front held aloft Italy’s national tricolour flag, a declaration that the march was a patriotic one. When they reached their destination – an unassuming apartment building – some knelt to lay a wreath or to leave a note. Then it was time to reassemble. ‘Comrades, Sergio Ramelli’, a man called to the crowd. ‘Presente!’, they roared back, celebrating the eternal presence of the dead (‘Here!’), hundreds raising their right arm in a rigid fascist salute.

This ritual – ostentatiously fascist in nature – did not take place in the 1930s, but in April 2024. Originating under Mussolini’s dictatorship as part of the cult of the fascist martyrs, the ‘Fascist ritual of the roll call’ became an annual event. In Milan this year, neofascists gathered to honour the far-right militant Sergio Ramelli, who died aged 19 on 29 April 1975. In recent years the ceremony has become increasingly national. Having traditionally provided an opportunity for neofascists from Lombardy to unite, in 2024 neofascist groups from across Italy came together, including CasaPound, Loyalty-Action and National Movement-Patriots’ Network. Roberta Capotosti, who works for Ignazio La Russa, president of the Italian Senate, was among the crowd who honoured the eternal presence of the dead, though she did not perform the salute.

The flame of fascism

Ramelli was a member of the youth division of the Italian Social Movement (MSI), a party founded in 1946 to keep the fascist flame alive in a constitutionally antifascist republic; its logo incorporated a tricolour flame, often thought to represent the flame that never goes out at Mussolini’s tomb. Ramelli died from injuries sustained in an attack by left-wing militants during a period of political violence in Italy between 1968 and 1988 known as the Years of Lead. More than 12,000 instances of political violence took place in public spaces during this era. Some attacks, such as the 1974 Brescia bombing, which killed eight and wounded 102, are now thought to have involved collusion between neofascists, Italian state intelligence agencies and the CIA.

Italy’s current prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, and president of the Senate, La Russa, are both founding members of Brothers of Italy, a far-right party that also incorporates the flame into its logo. They were also both members of the MSI youth. La Russa’s commitment to far-right politics continues a family tradition; his father, Antonio, was secretary of the Fascist party in Paternò, Sicily, leaving no question as to which Benito his son Ignazio honours in his middle name. Meloni joined the MSI at 15 and, after the party’s rebranding as National Alliance in the mid-1990s, took up a leadership role in the student division.

Although members of Meloni’s party do not generally partake in public performances of far-right heritage, they do make clear their support for its culture of remembrance and victimhood. In Meloni’s first speech in the Chamber as prime minister on 5 October 2022, she alluded to Ramelli’s death, telling deputies that the democratic right had always respected Italy’s republican institutions, even during the years of political violence ‘when innocent young men were killed with wrenches in the name of militant antifascism’. Six months earlier, on the morning of a party conference in Milan in April 2022, Meloni attended the official commemoration ceremony for Ramelli. Later that day, hundreds of neofascists marched to the site of his death where they performed the fascist salute.

Eternal life of martyrs

Throughout its existence – 1946-95 – the MSI used an emotionally charged notion of ‘remembrance’ to keep the fascist past alive in an antifascist republic. The language of martyrdom was a central part of this strategy. During the Years of Lead, MSI leader Giorgio Almirante honoured the far-right dead as ‘martyrs’ who had sacrificed their lives in the name of the party, presenting them as a minority persecuted by a dominant power. This narrative of victimhood sustains neofascist engagement today.

Stefano and Virgilio Mattei, sons of a local MSI leader in Primavalle, Rome, were two such powerful martyrs in the MSI’s pantheon. The brothers were killed on 16 April 1973 following an arson attack on their home by left-wing militants belonging to the group Workers’ Power. Virgilio, 22, and Stefano, ten, died at their bedroom window in full view of a crowd gathered at the foot of the building calling for them to jump to safety. The attack was quickly dubbed the Rogo di Primavalle. Rogo means ‘fire’, but it also translates as ‘pyre’ or ‘stake’, evoking religious or political sacrifice for crimes such as heresy or witchcraft. The term was first used the day after the tragedy by the right-wing newspaper Il Secolo d’Italia, a mouthpiece of the MSI, and was quickly adopted by others.

As the historian Thomas Laqueur has written, ‘biological death is more or less instantaneous’ but ‘social death takes time’. For the far right it takes an eternity, because its language of martyrdom immortalises. Although the left, too, honours its ‘martyrs’, the promise of eternal life goes hand-in-hand with the far right’s reverence of violence – a partnership that encouraged Italians to sacrifice their lives under the Fascist regime with the promise of status and public recognition. Mussolini was all too aware of the martyr’s powerful afterlife, and organised enormous ceremonies to honour the ‘fascist martyrs’, offering financial benefits and prestige for relatives of the dead. Each year fascists gathered in Florence to honour Giovanni Berta, thought to have been killed by militant communists in 1921. His name adorned monuments, streets and buildings. These ceremonies also took place abroad. Around 50,000 people attended the funeral procession held to honour two fallen Blackshirts on the streets of New York in 1927; their bodies had lain in state in the Bronx beneath a sign declaring: ‘For every black shirt that falls a thousand are born braver and truer.’

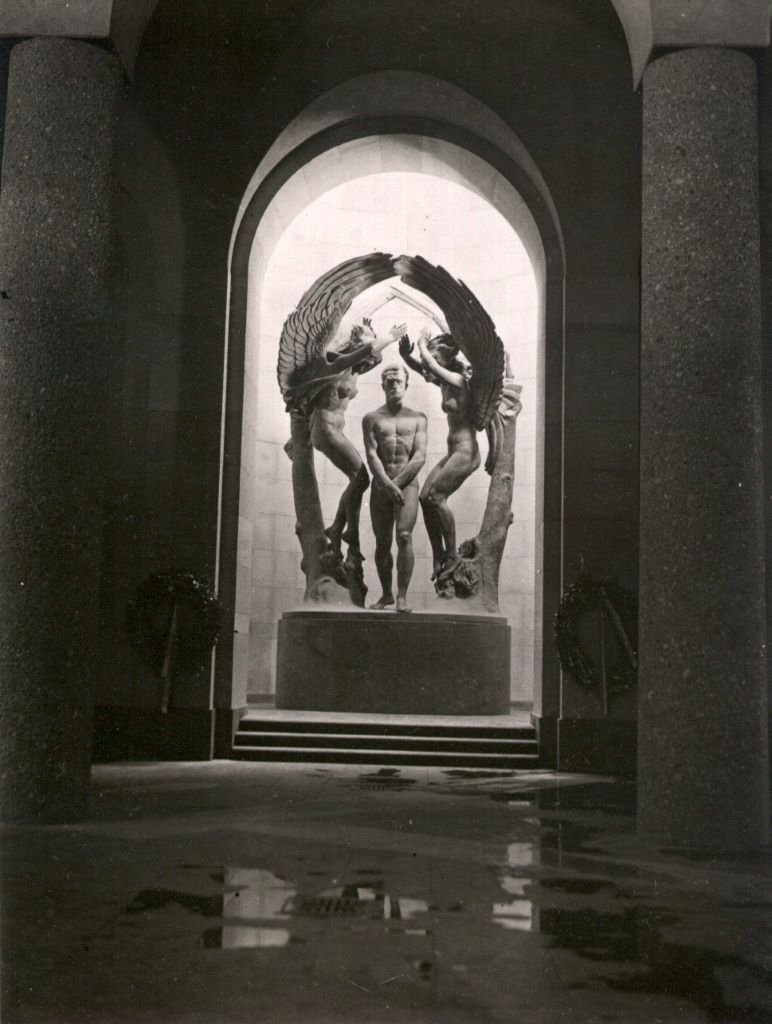

Mussolini’s fascists also claimed the First World War dead as their own, building large memorials to house the remains of men who gave their lives for the nation while knowing nothing of fascism. The Redipuglia War Memorial – unveiled in September 1938 – became the final resting place for 100,000 Italian servicemen killed between 1915 and 1917. Its 22 stone platforms are inscribed with ‘presente’ and declare the eternal life of these ‘fascist’ martyrs.

Memory culture

The monumental cemeteries which predated Mussolini – such as the Verano in Rome or Bologna’s Certosa cemetery, one of the oldest in Europe – became ‘arenas’ for political performances during the dictatorship, as Hannah Malone has shown. The Chapel of the Fascist Martyrs was unveiled at the Verano cemetery on 23 March 1933 as part of celebrations to honour the 14th anniversary of the foundation of the Italian Fasces of Combat, the predecessor to the National Fascist Party. At the unveiling ceremony, party secretary Achille Starace read the names of those buried within. The Chapel had space for 12 martyrs, but since only four Romans had died during fascism’s rise to power (1920-22), the remit had to be widened to include those who later died from injuries or illness. After hearing the names, the Blackshirt battalion lining the pathway in front called back: ‘Presente!’

Visitors to the mausoleum during the later 1930s would have been struck by the figure of Christ beneath a veil of black marble studded with crystals that stood upon the altar. Though the figure has since disappeared, a cross-shaped window still sits above the altar today, illuminating a dedication ‘to the fascist martyrs’, which remains. At ground level, a headstone-shaped plaque is dedicated to the ‘fallen for the honour of Italy’ during ‘Spring 1945’. Mussolini’s name is written in bold letters above the names of men who gave their lives in fascism’s dying days. At the foot of the plaque, beneath the evergreen cry ‘Presente!’, the names of the Mattei brothers, killed decades after the fall of the regime, have been added.

This inclusion, alongside Mussolini’s diehard faithful within a mausoleum built to honour those who died during fascism’s rise to power, shows the commitment of the far right – past and present – to broadening its pantheon. It is one example of the many monuments, memorials and reliefs bearing Mussolini’s name or image that still stand in Italy today, the legacy of its incomplete de-fascistisation process. On 7 January each year, neofascists walk through the cemetery, stopping to honour those claimed as part of Italy’s far-right heritage, including Goffredo Mameli, the Risorgimento-era patriot, poet and writer of Italy’s national anthem, whose death in 1849 predated Mussolini’s first rally in Milan by 70 years. Participants also honour the cemetery’s far-right victims from the Years of Lead, and those named in the Chapel of the Fascist Martyrs, where the procession ends.

‘For years now, we have chosen the Verano chapel as a symbol of all comrades who died on the path of honour’, Vincenzo Nardulli, a prominent neofascist in Rome, said in an interview with a far-right blog in 2019. Nardulli is one of two neofascists who received a five-year prison sentence after attacking a journalist and photographer covering the 7 January commemoration at the Chapel in 2019.

Remembrance

As residents in Milan earlier this year must have been aware, these events have given ‘mourners’ the chance to bring their contentious iconography and fascist rituals into public spaces under the guise of remembrance, a visible reminder of a persistent far-right subculture in an antifascist republic. What, then, is really being honoured as eternal when neofascists call ‘presente’: the dead, or the ideology that claims them?

Amy King is a senior lecturer at the University of Bristol and author of The Politics of Sacrifice: Remembering Italy’s Rogo di Primavalle (Palgrave Macmillan, 2024).

[ad_2]

Source link