Britain’s creepiest new horror stories

Alamy

AlamyBeginning with his acclaimed 2018 debut novel The Loney, the English writer Andrew Michael Hurley has spooked readers with his tales of strange rural communities – and now they’re moving to film and TV.

His publisher bills him as “the master of menace”, Stephen King is a big fan, and the film version of his third novel, Starve Acre, starring Morfydd Clark from Amazon’s The Rings of Power and ex-Doctor Who Matt Smith, has been shocking audiences across the US and the UK this year.

As the author of chilling literary fiction, Andrew Michael Hurley has earned a large following with his first three books – and is now releasing his fourth, short-story collection Barrowbeck. A British writer with an international readership, his debut novel The Loney was translated into 20 languages and earned stellar reviews: The Washington Post critic Nancy Hightower described it as “masterful” and “unsettling in the most compelling way”. Earlier this year, a small-screen adaptation of it was announced, which is set to be made by Jonathan Van Tulleken, a director of hit TV series Shogun and the upcoming show Blade Runner 2099.

Hal Shinnie

Hal ShinnieWork in the horror genre is rarely lauded for the quality of its writing, but Hurley’s novels have broken the mould, winning both plaudits and prestigious literary prizes. “Gothic has enjoyed quite a high literary status – if we think of the enduring classics like Wuthering Heights, Rebecca, Frankenstein – whereas books classified simply as ‘horror’ haven’t always been taken seriously, but I think that’s changing,” Hurley tells the BBC. “As we’ve looked back and reconsidered horror films from the 70s and 80s – say The Exorcist, The Wicker Man, Halloween – and seen some of them as works of art in their own right, then I think we’ve perhaps started to reappraise horror in general as being a genre that reveals something of ourselves to ourselves in a way that’s interesting and worth valuing.”

There is certainly a current surge of interest in horror – last year British publishing news outlet The Bookseller reported that sales of horror and ghost stories increased by 54% in the UK between 2022 and 2023, making it the most successful year for horror literature since records began. Dara Downey, a researcher and visiting lecturer at Trinity College Dublin with a special interest in the gothic and horror, says: “There’s a global horror boom at the moment, and perhaps what’s most notable about it is that, if social media is anything to go by, people are turning to the horror genre for comfort and escapism. I think it’s something to do with the fact that it’s a lot easier to watch or read about someone, say, being sucked into hell by a creepy girl in a white dress than it is to be bombarded with what we see on the news. People seem to be turning to horror as a way of getting a glimpse of other people’s nightmares as a form of respite.

“I think there’s a real sense of people needing to engage with writing that affirms our sense that the world is frightening and confusing, but also more enchanted and mysterious than the daily grind might suggest.”

Tales of rural isolation

All four of Hurley’s works are set in isolated rural communities in the north of England. “Isolation is a conscious choice,” he says. “I like to place my characters in spaces where they are cut off in some respects, where they have to rely on their own resources and on each other. Weird things can happen in those places that haven’t been disturbed by development or progress or modernity in quite the same way that a town or a city has. There are ways that history can be unearthed, either literally or metaphorically, so that the past seems to exist quite close to the surface.”

In Hurley’s universe, the countryside is a hard, implacable, unnerving place. The sort of place where unspeakable things happen up on lonely moors and down in dank cellars. Where threatening locals force their way into houses to enact ancient ritualistic plays. Where people still believe in the power of witch bottles and are perhaps right to do so. Where either nothing grows because the land is cursed or where trees mysteriously fruit at the wrong time of year. Rare is the country fair that doesn’t end with a pony stabbed or a man blinded by a horse’s kick or a girl placed under an enchantment by a sinister clown. “What did you expect it was going to be like here? Roses round the door and cows in the buttercups?” one of Hurley’s country folks sarcastically asks of an outsider in his second book, Devil’s Day.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAndrew Michael Hurley was born and grew up in Preston in North West England. He and his family would holiday in Cumbria and Yorkshire, in the sort of rural, rugged landscapes dotted with smallholdings that he now writes about, and he would seek out books of local ghost stories wherever they went. He has worked as a teacher and a librarian, lived in London and Manchester, and is now based back in the Preston area, teaching creative writing at Manchester Metropolitan University in addition to his own writing career. Extraordinary though it seems given the accolades he has received, he initially struggled to get his first novel published.

In The Loney, the congregation of a church go on a religious retreat to a bleak house in a desolate place inspired by Morecambe Bay in Lancashire. The book describes the area as: “A wild and useless length of English coastline. A dead mouth of a bay that filled and emptied twice a day.” The pilgrims hope a week of prayer and a visit to a local shrine will cure the mute brother of the teenaged narrator. But there are some sinister locals who seem to be up to no good. The story draws on folklore, ritual and superstition. The landscape – at best, indifferent to human suffering and, at worst, a gleefully malevolent cause of it – is absolutely integral to the story. Hurley skilfully creates an atmosphere of mounting unease that builds to an indelible climax conveying a sense of real evil.

He spent several years working on the book, but when he sent it to publishers and agents he was met with either rejection or silence. Eventually he tried Tartarus Press, a small independent imprint specialising in weird fiction. “When Tartarus emailed me, having read the manuscript, to say ‘Yes’, it was a very strange moment,” Hurley says. “I read the email several times to make sure it was real.”

Tartarus editor Rosalie Parker says: “When I first read The Loney I knew that its atmospheric blend of the supernatural and the psychological made it a perfect Tartarus Press book, and like all our books I was sure that it had the potential to be a wider commercial success if the stars aligned.”

Alamy

AlamyThe stars moved smoothly into place. The book was published in 2014 and, despite having a tiny print run, it came to the attention of a much larger publisher, John Murray. It was reissued and ended up winning the Costa first novel award and the Book of the Year at the British Book Industry Awards. Stephen King contributed a blurb: “The Loney is not just good, it’s great. It’s an amazing piece of fiction.” Meanwhile, Van Tulleken has described it as “an absolute gift for a director”.

His horror inspirations

So where did it come from, this strange book that Sarah Perry, the author of the brooding, gothic The Essex Serpent, called “a masterpiece” when reviewing it in The Guardian?

“I loved Stephen King, James Herbert, Clive Barker, when I was growing up,” Hurley says. “I devoured them when I was 14, 15 and then I started trying to write my own stories in that sort of style. I’m not sure there was a great deal of literary merit to them but there was a lot of murdering and blood and vampires.” He also enjoyed classic horror films such as the aforementioned The Wicker Man, Don’t Look Now and The Omen.

“And there was lots of strange stuff on television,” he says. “I think it was perhaps a little bit more out there and daring than TV is now. You’d switch on TV late at night and come across something weird and then think, ‘What the hell was that that I just watched?'”

He was particularly keen on the work of Nigel Kneale, an influential UK screenwriter whose 1970s output included two television plays, Murrain and Baby, which were set in isolated rural settings and featured many of the “folk horror” elements that appear in Hurley’s work.

“I think what I love about Kneale is the doubt and uncertainty that you’re left with after watching or listening to his plays,” says Hurley. “He’s very resistant to explaining too much. I’m a huge fan of writers like Robert Aickman and Shirley Jackson who are very similar in that respect. They don’t over-explain, they don’t give you the solace of saying, ‘It’s OK, we can think of it this way.’ Those are the stories that haunt you. That’s something I really try to emulate. If people go away with more questions than answers, I feel like I’ve done my job properly.”

Whatever the shortcomings of his teenage stories – and he later also wrote two novels set in London which he says were “horrible pastiches” and which will never see the light of the day – readers and critics agree that his published work is of the highest order.

Devil’s Day, about a newly-married couple expecting their first child who return to the farm on which the husband grew up in order to help with the annual “gathering” of the sheep (bringing the flock down off the moors in the autumn), won the 2018 Royal Society of Literature Encore Award for Best Second Novel, and was picked as a book of the year in five British newspapers.

John Murray Press

John Murray Press“The nebulous presence of the Devil is evoked so palpably in this novel that at times I hardly dared look up when reading for fear of seeing him grinning at me from the chair next to mine,” Jake Kerridge wrote in the Literary Review.

In Starve Acre, his third novel, published in 2019, Juliette and Richard live in a moorland farmhouse and are grieving over the death of their young son. Juliette seeks comfort with a group of occultists because what harm ever came from that? A film version, starring Morfydd Clark and Matt Smith, was released in cinemas in July in the US and September in the UK. Its director, Daniel Kokotajlo, used a variety of techniques to make the film look as though it had actually been made in the 1970s like the Kneale plays that both he and Hurley admire. “We spent a long time working on how to capture that feeling,” he tells the BBC. “We watched a lot of old horror films and weird British TV. Part of it was down to the lighting and I also found some amazing old 1970s lenses that created a little bit of distortion on the image that looked fantastic.” He sees Hurley as the contemporary heir to authors such as famed Victorian ghost story writer MR James.

Why scary stories are booming

“The legendary director Wes Craven said, ‘Scary movies don’t create fear, they release fear,’ and I think that goes a long way to explain the rise in popularity of the horror genre in the world of books, and why some of those books, such as Starve Acre, have been adapted into excellent films,” says Yassine Belkacemi, editorial director at John Murray Press. “Horror is an effective prism for writers to explore our world, our ears, our subconscious, when the reality of everyday politics, news, and society can be overwhelming. Especially in the US, which is going through an extremely polarising time when it comes to many issues, the world of horror, ironically, seems to have been a genre to explore the country’s greatest fears whether that be the work of Shirley Jackson, Stephen King or Jordan Peele.”

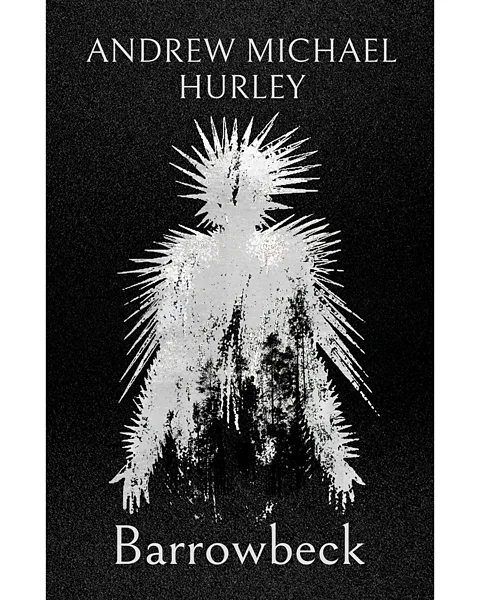

Starve Acre completed what Hurley thought of as a loose trilogy about landscape and responses to it. The new book, Barrowbeck, further cements his reputation as Britain’s creepiest author, but also marks something of a departure. It is a collection of 13 linked, chronologically-arranged short stories – some of which began life as stories on BBC Radio 4 – about life in a valley in the north of England. “There are some stories that are folk horror, there are others that lean more into fantasy and science fiction,” Hurley says. The collection begins with the tale of the establishment of a settlement in the valley in the distant past and ends with a piece set in the near future when the valley has been ravaged by climate change.

“I enjoyed writing that story although it is quite depressing to think about what our future might look like,” says Hurley. “I’ve been reading a lot of apocalyptic, environmental disaster fiction – John Christopher’s The Death of Grass, for example. An incredible book. It’s a genre of writing I would like to revisit.”

His next novel, expected to be published late next year, also breaks new ground for Hurley, with an urban rather than a rural setting. The central character is in a decaying seaside town out of season, recalling a summer holiday there years ago. However, it would seem a fairly safe bet that this particular seaside holiday won’t be all ice cream, sandcastles, and innocent fun in the sun.