How to choose the best – and most eco-friendly – swimwear

[ad_1]

Alamy

AlamyMake a splash this summer – from luxury vintage to sustainable fabrics, here’s our smart guide to swimming in style.

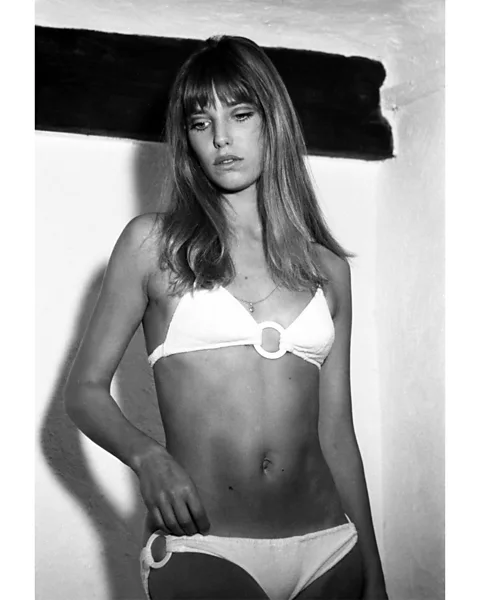

It’s at this time of year when images of Jane Birkin in a ring-fronted bikini or Brigitte Bardot in her classic frilled bikini bottoms resurface. Swimwear brands name their designs after iconic stars, with vintage styles reworked into modern pieces. Remember Julia Roberts’ cut-out white and blue dress in Pretty Woman? Swimwear label Hunza G, which celebrates its 40th anniversary this year, created the garment from its trademark crinkle fabric.

Alamy

AlamyLike swimwear’s timeless styles, the environmental damage it causes also endures. The problem comes down to plastic. Swimsuits need to stretch, recover their shape, and be quick-drying. Therefore, synthetic fibres like nylon, polyester and elastane, which are derived from fossil fuels, are the most widely used materials, both for performance and low cost. But the washing of synthetic products leads to the accumulation of more than half a million tonnes of microplastics on the bottom of the oceans every year. And poor-quality bikinis don’t last long, with the cheap, fast-fashion business model encouraging multiple consumption every time we go on holiday. It remains hugely difficult to recycle swimwear, so unwanted swimsuits contribute to the 100 billion items of clothing produced globally, of which 65% end up in landfill within 12 months.

It wasn’t always like this. Until the 1930s, all bathing suits in the US and Europe were made from natural fibres, in particular wool, says Kevin L Jones, senior curator at ASU FIDM Museum in Los Angeles. “We even have some tightly-woven silk bathing suits in the museum,” he tells the BBC. “But there was also a difference of mindset then. Materials were valued and utilised until they couldn’t be used anymore. Only a small percentage of the very wealthy could replenish their wardrobes. Often, people made their own bathing suits.”

Alamy

AlamyAs manufacturers grappled with the sagging element of wool once it became wet, the breakthrough came from the United States Rubber Company, says Jones, which introduced Lastex into the market, a type of elastic yarn that could be blended with other fabrics. “You couldn’t patent wool, silk and hemp, but you could patent the technologies being developed,” Jones explains. “And that’s what led to the major boom industries within chemicals that have affected our clothing ever since. That’s how we ended up with all the polyester and elastane, and with a throw-away mindset.”

But the tide is turning again – albeit slowly, and not exactly in the same direction – as some swimwear brands and manufacturers innovate with better practices and materials. One such fabric is Econyl, made using synthetic waste such as discarded fishing nets, and then recycled and regenerated into new nylon fibre.

Swimwear label Stay Wild is one of the brands making its collections from Econyl, at a small factory in London. “We use a slow-fashion model, going against traditional fashion seasons,” co-founder Natalie Glaze tells the BBC. “We launched with one collection in the first two years. We also introduced pre-orders to minimise waste, use deadstock in our collection, and make high-quality pieces that last longer to encourage buying less but better.”

Stay Wild

Stay WildEconyl isn’t a perfect solution – microfibres are still shed in the washing process – but there are methods to minimise the shedding. The best way to look after swimwear is by gentle handwashing, which reduces the release of microfibres. Given that most swimwear is worn for short periods at a time, they require less machine-washing. But when they do, using a wash bag or a filter in the washing machine helps.

A bigger splash

Swimwear is also joining the second-hand clothing world. “We are increasingly seeing the preloved market evolve, and I have definitely seen the rise of swimwear in the category,” says Clare Richardson, founder of pre-loved online retailer Reluxe Fashion. “A few years ago, people wouldn’t buy pre-loved shoes, and now they are one of our biggest categories. Pick the level you are comfortable with – is it something new with tags, or perhaps you’re comfortable with the concept but want to steam and wash more thoroughly when it arrives.”

Richardson advises customers when buying second-hand luxury swimwear to choose retailers that fully authenticate their garments. At Reluxe, she doesn’t accept pieces with stains and visible wear-and-tear, while any “faults” are photographed and detailed on the website.

Paris and London-based photographer Isabelle Hardy buys her swimwear from online marketplaces Vinted, Depop and Vestiaire Collective, but her best find came from eBay. “Years ago I bought a beautiful, vintage one-piece that was – and still is! – in great condition,” she recalls. “I was drawn to it because it’s very Hunza G in style but I couldn’t afford the brand at the time. If you search resale sites, there are lots of people selling unworn pieces of swimwear, even with tags on.”

Reluxe Fashion

Reluxe FashionFor many people, the main issue with buying second-hand swimwear is – understandably – cleanliness, so being able to inspect a garment in person helps to validate its quality. Thrift stores are a favourite of sustainability advocate Jemma Finch, who last purchased swimwear a year ago from a vintage clothing store in Wimbledon, south-west London. “You can often find high-quality, gently used pieces at a fraction of the cost of new ones,” she says. “Plus, many thrift stores thoroughly clean and sanitise their items before selling them, so you can be confident in their cleanliness.”

Holly Watkins, owner of second-hand clothes store One Scoop Store in northeast London, uses a cup of soda crystals in the washing machine to remove stains on lighter colours. “We won’t re-sell swimwear without washing it first,” she says, adding that up to 70% of the swimwear she sources is actually new with tags. “Shopping preloved means you can go for a brand that you might not usually be able to afford. I think it’s worth spending a little more for good swimwear, which will last. We also source a lot of deadstock vintage swimwear with the labels on.”

Swimwear tips

– For timeless 1960s styles, search vintage sites and stores

– Many luxury resale sites offer unworn designs, still with labels

– When buying new, check the eco credentials of the brand

Stay Wild takes back old, worn-out swimwear from any brand that would otherwise end up in landfill and recycles them into industrial products, such as carpets. But the brand’s ambition is circular: to recycle old swimwear back into new swimwear, and it has already made a fully circular swimsuit. After nine months in development, the brand created its own material and a prototype of a mono-constituent garment (in which one main constituent is present to at least 80% of the composition), without any elastane.

“By removing the need for elastane, we have created a fully circular piece that can be recycled again and again and again,” says Glaze. “However, like with many new innovations in the industry, this technology is a huge cost, so commercially it doesn’t make sense to launch this yet, but we are exploring other avenues and how to make this goal a reality.”

Anne Prahl, founder of Circular Concept Lab, a collaborative platform for sharing and implementing circular design tools, believes that the future of sustainable swimwear lies in the commercialisation of textiles-to-textiles recycling, with elastane currently the major obstacle. “Sportswear retailer Decathlon is doing great work in this area and the company already sells a swimsuit made from recycled and recyclable fabric,” she explains.

Alamy

Alamy“Decathlon replaced the elastane in one of its swimwear ranges with a mechanical stretch fibre developed by The Lycra Company. The recyclability process is currently being tested with recycling partners.”

Encouragingly, says Prahl, Lycra’s work with textile recyclers on technologies for recycling blends – the other major barrier for textile-to-textile recycling – shows that the Lycra’s T400 fibre does not disrupt the recycling process when blended with other materials.

For Jones, sport has always led – and continues to lead – innovation within the wider fashion industry. “Athletes can test out in extreme ways if something is going to work or not, all around the world,” he says. “Now Artificial Intelligence (AI) is going to influence this space. It’s going to create remarkable things, but it will wreak devastation, too. I don’t know what these will be. But, looking at it through a historian’s eye, we are repetitive.”

For now, options for buying better swimwear are certainly growing. Perhaps through the choices we make today, consumers will help contribute towards shaping this moment in time and – ultimately – how history judges it.

Three Things to Help Heal the Planet by Ana Santi is published by Welbeck Balance

[ad_2]

Source link