[ad_1]

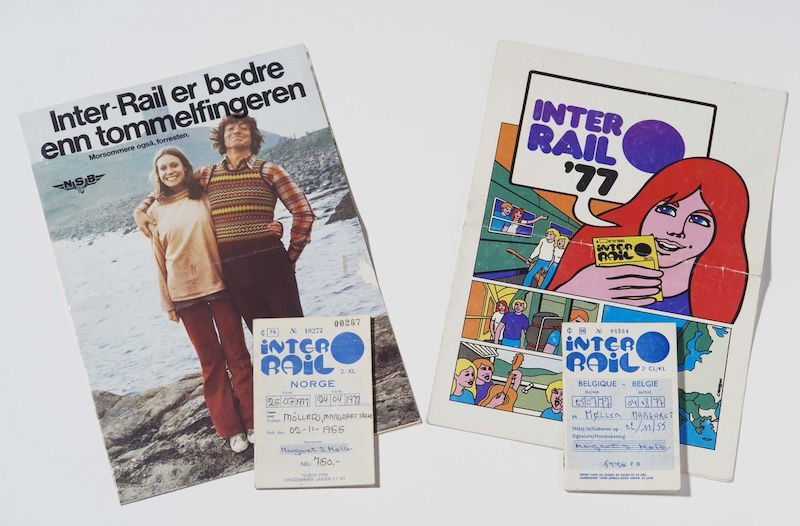

It’s 1972, you are in your late teens, and you see a poster at your local railway station which promises one month of unlimited train travel in 20 European countries for £27.50. Would you have been tempted? Perhaps you were one of the almost 88,000 backpackers who purchased an Interrail pass and took a trip during that first year of the scheme.

Originally conceived as a one-summer offer to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the International Union of Railways in 1972, demand from young travellers led to Interrail passes being offered again the following year. The scheme has continued ever since. Interrail was not a new concept, however; non-Europeans had been able to purchase a similar Eurail pass since 1959. Offering first-class travel at student-friendly prices, Eurail proved so popular – particularly with young Americans – that it had to be downgraded to second-class in 1971, largely due to complaints from disgruntled passengers unhappy at sharing their premium carriages with international backpackers. With Eurail a second-class offer, it was difficult to justify the continued exclusion of Europeans from budget rail travel. Interrail was born.

Europe Endless

The origins of young adults exploring continental Europe can be traced back to the Grand Tour. These leisurely circuits of Europe were usually undertaken by men from the upper classes, mainly, but not exclusively, from Britain. The classic route headed south, through France, towards what is now unified Italy. The Grand Tour’s heyday ended with the French Revolutionary Wars in the late 18th century, but it was the spread of the railways that finally finished this laborious form of ‘slow travel’. In 1834 it had taken Robert Peel 12 days to return from Rome to become prime minister. By the 1860s, the Eternal City was only 60 hours from London.

One person who saw the potential of the burgeoning railway network was Thomas Cook, a Baptist minister turned businessman. In 1841 Cook persuaded the Midland Counties Railway to run a service from Leicester to Loughborough to transport 500 passengers to a temperance meeting. In the decades that followed Cook’s range of tours expanded, first to cover much of Britain and Ireland and then to continental Europe, beginning with a circular route which included Brussels, Cologne, Heidelberg and Paris. Cook’s organised tours appealed to a middle-class clientele curious to explore Europe with their needs taken care of.

I have conducted extended interviews with 52 travellers from across the UK who took an Interrail trip between 1972 and 1997. These discussions revealed that a Cook-type tour was anathema to backpackers, who cherished the freedom the pass seemed to offer. As one Interrailer, Kausar, told me: ‘Because we had the ticket we felt we could go anywhere we wanted to go.’ Despite this, one of Cook’s practical legacies was inescapable. More than 100 years after Cook’s Continental Timetable was first published in March 1873, later editions of these well-thumbed volumes would become an essential reference point for thousands of Interrailers. Anita and Neil’s copy of the timetable was already three years old when they set off in 1989, but they used it to work out where they could get to from any particular place.

A quirk of the Interrail story is that its temporary decline in the 1990s coincided with the opening of the former Eastern Bloc to foreign tourism. From a high point of almost 372,000 passes sold in 1990, just three years later sales had fallen to under 132,000, remaining at similar levels for the rest of the decade. This was partly due to the Yugoslav Wars. The long and often uncomfortable train routes through the Balkans used by thousands of backpackers as a cheap way of getting to Greece became either unreliable or hazardous.

But the sharp decline in Interrail’s popularity cannot be attributed solely to the break-up of Yugoslavia. In the 1990s the original ‘one size fits all’ ticket was replaced by a range of options which made the scheme more difficult for travellers to navigate. Interrail was extended to adults of all ages (albeit at higher price points) and zonal passes covering fewer countries were introduced. This second change was partly forced on the scheme when cracks in the unity of Europe’s rail operators began to emerge. In 1992 France, Italy, Spain and Portugal all threatened to exit the scheme, mainly due to their longstanding frustrations at transporting a disproportionately high number of Interrailers from northern Europe. As noted by The Observer in August 1992, the French ‘were particularly sensitive to having their rail network clogged up with backpackers in July and August’, to which British Rail’s bullish response was to suggest travellers ‘go east’ instead.

Encounters

The travels of young backpackers inevitably coincided with events shaping Europe, even if they were not always aware of them. Tim was one of the pioneering Interrailers in 1972. Midway through a journey which included Scandinavia and Greece, he and his friends spent a day in Munich while the city was hosting the Olympics. Tim described the atmosphere as ‘jolly’ as they strolled around the perimeter of the Olympic Stadium, but this was to change three days later with the deadly terrorist attack on members of the Israeli team. Tim only learnt about the Munich massacre sometime after the event when he saw a headline in an out-of-date English newspaper, probably in Athens. Gordon, a solo Interrailer, recalls visiting Zagreb in 1995 where he photographed an impromptu war memorial displaying the names of victims from the recent conflict. Only after returning home did he learn that, during his visit to Croatia, the situation in neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina had deteriorated, culminating in the Srebrenica massacre.

While most Interrailers avoided serious trouble, a significant proportion described encountering dangerous situations. At worst these included physical or sexual assault, mugging at knifepoint and being locked in buildings against their will. In 1974 Maurice was awoken on the floor of a Spanish railway station by some sharp kicks to his ribs. Reacting instinctively, he grappled with his assailant only to discover it was a policeman. He spent the rest of the night in a cell. As they reflected on these uncomfortable events up to five decades later, it was not uncommon for interviewees to blame their own youthful naivety. Discussing persistent unwanted attention in Yugoslavia during her 1978 trip, Aileen acknowledged the cultural differences of the time and added: ‘We were probably walking around in shorts and halter necks and stuff. You know what I mean?’ Others preferred to focus on the acts of kindness they received. Penny recalled how she and her friend Janie were saved from spending a night on the streets of Venice in 1974 when a medical student took them to a local convent where beds were provided to those who had nowhere else to go.

Out of sight

Young travellers from the UK took an estimated 500,000 Interrail trips during the first 25 years of the scheme. Given this figure, the absence of Interrail from accounts of British youth culture is notable, especially compared to the volumes that have been written about parallel cultural trends such as hippy, punk and rave. These movements were relatively short-lived and inextricably linked to the music or fashion of the time. They also became newsworthy, gaining a degree of notoriety due to perceived associations with anti-social behaviour. Interrail was the antithesis of these cultural phenomena because it achieved longevity and became hugely popular without ever becoming fashionable in the traditional sense. Interrailing took place out of sight and in an era before any mishaps could be relayed home with a few taps of a screen. This meant that it rarely attracted media interest. That is, until 1994.

To address the sharp decline in sales of Interrail passes in the UK, in June 1994 British Rail booked a series of full-page advertisements in several national newspapers. These adverts paired an edited image of the European flag in which the 12 gold stars were replaced by rolled condoms with the provocative headline: ‘Interrail: You’ve got the rest of your life to be good.’ The advert included a call to action to book an Interrail trip in 1994 to coincide with the year of ‘Europe Against AIDS’. In the furore that followed, the adverts were withdrawn after appearing in the Guardian and the Independent. The Daily Mail opined that: ‘It is sad that some newspapers which claim to moral integrity can collaborate in such tackiness.’ Virginia Bottomley, Secretary of State for Health, expressed her view that the advert was ‘in poor taste’. According to Marketing magazine, by October the campaign was the most complained about advert of the year, provoking more than 160 letters.

Taking the train

Controversies aside, by its third decade the Interrail scheme was already out of step with the zeitgeist, partly because the mid-1990s generation could travel in new ways. Cheap flights offered quicker access to Europe; EasyJet, a company that has since become near synonymous with this type of travel, was launched in 1995. Just as youth mobility was being explicitly promoted in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, young travellers were turning away from Interrail. Nevertheless, the scheme has bounced back in the 21st century. In 2018 the European Union recognised Interrail’s contribution to education and development by incorporating free passes into its Erasmus Programme. Then, in October 2023, the Chair of Eurail, Alexander Mokros, announced that combined sales of Interrail and Eurail passes had exceeded one million for the first time in a calendar year. This milestone highlighted that the scheme is no longer the preserve of the young with 40 per cent of these purchases being for adult or senior passes. It would appear that the generations who were captivated by Interrail in its formative years are packing their bags and taking the train once again.

Ian Lacey is a Postgraduate Researcher at Royal Holloway, University of London.

[ad_2]

Source link