[ad_1]

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFrilly, hyper-feminine and cute with bows everywhere, coquette style is increasingly popular. As an aesthetic, is it a problematic trend – or fun and empowering?

In 2024, makeup is coquette; our dogs are coquette; rooms are coquette. From the office to the gym, bows are appearing in places where they wouldn’t dare before. It’s as if Gen Z and younger millennials have found a way to wear Sofia Coppola films, from the pastels, lace and A-line silhouettes of 2006’s Marie Antoinette to the stockings, Mary Janes and Peter Pan collars of 2023’s Priscilla. Now, musicians like Sabrina Carpenter and Chappell Roan are confidently taking the stage in pearls, lace and corseted tops, while other celebrities like Sarah Jessica Parker, Sydney Sweeney, and Cardi B have casually nodded to the coquette aesthetic with a simple bow.

With its high-profile reach and its longevity, coquette has arguably surpassed the status of a micro-trend and become, if not quite a movement, then a community – and a topic of controversy.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhat is coquette?

Before we step ballet-flat first into this trend, what is it, exactly?

A coquette is defined by the Oxford English dictionary as “a woman who trifles with men’s affections” or “a woman given to flirting or coquetry”. However, according to influencer and stylist Maree Ellard, the movement separates itself from its literal definition, in a sort of reclamation of femininity, especially for its Gen-Z audience.

“I think people who are not aware of coquette are going to think that it means wearing flirtatious, promiscuous and hyper-sexualised pieces for attention. However, if you are in the coquette community, or understanding of it, you realise that it is an incredibly hyper-feminised, almost nostalgic view of girlhood and youth, before things became so complex,” Ellard tells the BBC.

Getty Images

Getty Images“We are also in this kind of political climate in which the sexualisation of female bodies is so front of mind. That’s why I think that it’s a big thing for Gen Z. It’s them [fighting] back and saying, ‘I’m not dressing for you, I’m dressing for me. But dressing for me doesn’t necessarily mean that I cover every inch of myself.'”

Still, the trend has had trouble escaping not only the implications of its definition, but also the historical associations of the look. Coquette exists at a crossroads of being, on the one hand, problematic, and on the other, empowering. Its proponents view coquette as a triumph over the male gaze, and a reclamation of femininity. But critics point to a lack of inclusivity and undercurrents of infantilisation and docility.

“Many fashion trends that stand out as being something a bit ‘different’, [tend to] exclude let’s say fat bodies, hairy bodies, black bodies, non-binary bodies. They’re usually pinned to templates of thin, cisgendered female whiteness. It’s almost as if having that body gives you the right to play around with anything you want. Then, in order for other bodies to take it on, they’re doing something ‘extra’. Then it becomes little bit more difficult, and it’s also then little bit more ‘radical’,” says Meredith Jones, professor of Gender and Cultural Studies at Brunel University London.

Netflix

Netflix“So if a thin, white 18-year-old dresses in ribbons and bows, it’s going to be a tiny bit controversial, but not hugely,” Professor Jones tells the BBC. “But if her fat, black counterpart, does it, then she’s got a whole lot more work to do around answering people who say this is unacceptable.”

And it seems as though many influencers agree.

“As somebody who perused a lot of darker sides of Tumblr when they were a teenager who was very confused and self-conscious, I can tell you just from memory that a lot of the inspiration content for losing weight was inadvertently very much themed like this: very dainty, very pastel very pearlescent,” says TikToker Addy Harajuku, who has also expressed concern for an “extreme [disordered eating, often referred to as ED] community” that she’s seen grow alongside coquette. “It is not everybody in this community that is like this. In fact, it was always a vocal minority that ruin it for the majority,” she adds.

Blair, another TikTok creator, has shared a similar experience and sentiments in a TikTok video: “If I were to try to get into that community and not just watch from far back… I have a very deep feeling that I would be used as ‘fatspo’. Unfortunately, I would look at things like ED Tumblr and ED Twitter years ago and they pretty much all were coquette girlies… I know everyone with that style isn’t like that, but it is definitely a big, unfortunate part of it. There’s also a very limited collection of plus-sized clothing in that type of style.”

Alamy

AlamyWhat these creators and commentators have observed as trends within the community lend themselves to an even more prominent piece of the coquette conversation. Such a strained emphasis on petiteness, and seemingly stereotypical “girliness”, has led many to draw parallels to darker themes.

“I was around in the Tumblr era, which is really where [coquette] has its origins. You really have two sides of the fold there. You had the coquette, which was the bows, the frilly, the girly, the romanticisation of girlhood leading into womanhood and all its complexities. And then you have the other side, which was very much glorifying age gaps, using sexuality as power and unfortunately glorifying the movie and book Lolita, which is quite a troubling thing.” Ellard explains.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEllard is referring to Lolita – not the Japanese subculture inspired by Victorian-era fashions – but the 1955 novel by Vladimir Nabokov in which a middle-aged literature professor (and unreliable narrator) grows obsessed with a 12-year-old girl. The novel led to pop culture references that glorify some of the ideas presented in the book.

The online community known as “nymphette”, a sub-category of the coquette aesthetic, has also led to debate. The community claims no associations with Nabokov’s novel, but “is not far from paedophilia through buying into and sometimes sexualising childish fashion trends, and romanticising related topics,” writes Iustina Roman in the University of Oxford’s Cherwell student newspaper, in a piece titled The dark side of coquette. Roman also adds that coquette aesthetics that champion innocence and hyper femininity are in danger of being criticised as catering to the “male gaze”.

She and many influencers, however, assert that this should not be blamed on those who participate in the trend, but rather on those whose oversexualisation of women has grown so overwhelming and constant that it prompted this attempt at subversion in the first place.

“It’s an aesthetic, it’s something we dress up and have fun in. At the end of the day, you are blaming women for the male gaze. It’s literally just a return to girlhood, and I think that it’s really wrong that we are responsible for men’s problems ” commented content creator Sophia Hernandez in a recent video.

“I think there’s merit to any criticism,” says Professor Jones. “It’s always worth discussing these things, but something as complex as what many different sorts of people decide to wear can never really be narrowed down to one thing. I don’t think you can particularly say this is feminist or non-feminist, good for girls bad for girls, a way of attracting boys or a way of repelling boys, I just don’t think it can ever be that simple. It’s about playing with different looks, playing with different identities. Having the freedom to experiment and try different things.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn defence of coquette

Nymphette may share coquette’s affinity for bows, lace and ankle socks, causing critics to draw a connection between coquette and Lolita, but, as Ellard argues, coquette exists as an umbrella term for a certain set of separate subcultures.

“I’m not sure there is a trend that’s its parent, really. Even with things like punk, emo and scene you’ve got that kind of linear evolution of where they spurred from. But coquette is almost like a true origin. It just got named and people ran with it. It’s a very specific name for girly, youthful fashion. And I think because that’s the name that’s really stuck, that’s become the parent title. And then you’ve got all the ones underneath it.”

This is not the first time we’ve seen coquette, or even an aestheticisation of “cute”. Brands like Sandy Liang, Miu Miu, Shushu/tong and Selkie have been embracing coquette-esque elements far longer than coquette has had a name. John Galliano has also been known to showcase versions of this trend in his work since as early as his “Fallen Angels” collection in 1986, with puff sleeves, empire waists, and lace detail. And the same late baroque influence that inspires some of coquette has found its way to Vivienne Westwood pieces for decades, notably in her 1995 Vive la Coquette collection. More recently designers including Molly Goddard, Simone Rocha and Sandy Liang have embraced the look.

Getty Images

Getty Images“Looking further back historically, we can identify when particular components of this fashion mood were previously fashionable,” Amy de la Haye, professor of Dress History and Curatorship and joint director of Centre for Fashion Curation at London College of Fashion, UAL, tells the BBC. “If we take just one element – the neck choker – these were being worn in portraits of Anne Boleyn (1507-1536) and, in a very different vein, during the French Revolution when blood red chokers were worn by anti-revolutionary Merveilleuses as a sartorial protest for those sent to the guillotine.

“They were the height of chic in Victorian and Edwardian times and revived again in the 1930s. Diana Vreeland famously wore a black velvet ribbon choker with a red rose bud tucked into it to accessorise her new black sequin trouser suit from Chanel in 1937. Many other elements – lace, lingerie styles as outerwear, corsetry, bows – were all very fashionable in the late 1930s, as was the dinner suit, which this style also references.”

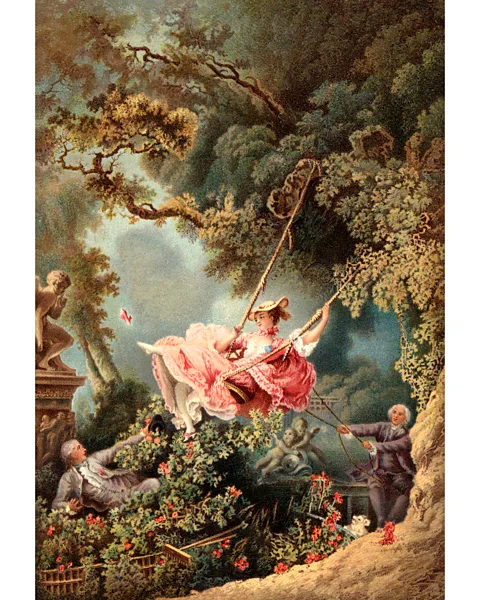

Jones adds that some more contemporary adaptions of the coquette style draw inspiration not only from Rococo fashion, but from other artistic media of the era. She references Jean-Honoré Fragonard‘s The Swing (1767), an oil painting in which a woman donning pastels, lace and bows is depicted kicking off a kitten heel at the apex of a velvet-cushioned swing.

“To me, it looks like nothing new. Maybe it’s new for some of the young women who are doing it. But there have really always been these kind of ultra-girly, ultra-feminine modes for women and girls to choose to present themselves in. I don’t imagine that the current meanings are any different to what they’ve been for at least 100, if not 200 years,” she adds.

Coquette is a fashion mainstay, and the key to its popularity, and to its relative longevity, may lie in its simplicity. According to Ellard, real coquette should have no hard-and-fast rules, specific brands or price points. It should simply mould to whatever the wearer likes and has access to.

Alamy

Alamy“It’s easy to do and it’s easy to adapt. Sometimes it’s as simple as colour choices like pinks, lilacs, whites and ivories,” says Ellard. “Things that many were already familiar with wearing as a child or as a young adolescent. There is that familiarity, that nostalgia to it. It’s youthful, it’s girly, it’s pretty, it’s simplistic, but then you’re able to hybridise it so simply with other interests. When you add bows to something, you have the coquette thing kind of covered.”

From “dollette”, “cottagecore” and the gingham of “vintage Americana”, to the melding of “bloke core” and coquette to form “bloquette”, coquette feels less like a fleeting fad, and more like a term that encompasses things that are “girly”. And participants are tailoring or customising it however they wish.

According to Ellard, this customisation is typically linked to what’s popular in culture. Coppola films, Bridgerton and episodes of Euphoria have all influenced the trajectory of the coquette movement thus far, and Ellard says she hopes to see the trend push its limits, potentially even taking a sci-fi turn one day. It’s this kind of potential, paired with the core coquette community, that leads her to believe that coquette will stick around for a “very, very long time”.

Getty Images

Getty Images“I tend to put aesthetics in one of two categories. One category is, for example, you’ve got the punk and hippie [subcultures]. They come from movements and form communities. They were signifiers of similar values and beliefs. And then… on the other end of the spectrum we’ve got all these aesthetics where there is so much content to consume that there’s actually not much substance behind it,” says Ellard.

“Coquette is super interesting because I feel like it sits in the middle. It’s an aesthetic-first kind of thing, and I wouldn’t say it comes with built-in values like punk. However, it almost comes with built-in interests and activities which I think brings a sense of belonging to a lot of people. You’ve got films you’re going to like, you’ve got music that you’re going to be into. It translates to interior design and activities like journaling. It almost marks a turning point to the aesthetics without substance that we see now. It doesn’t have the origins of a political movement, but I think it definitely brings a sense of belonging.”

[ad_2]

Source link